The Security and Climate Nexus

Accelerating the green transition can bolster national security while protecting the environment.

April 2023

Climate change is widely recognized today as a threat to global stability and a risk multiplier for national security. In recent years, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the United States government, and the European Union (EU) have published strategies and policies acknowledging and addressing the risk to collective and national security that climate change poses. The Fragile States Index, along with other organizations monitoring conflict, humanitarian crises, and fragility as part of their mandates, have identified climate change as a key threat to human rights—including the right to life—and socioeconomic well-being. Mitigating and adapting to the impacts of climate change will be key to ensuring that future security strategies keep pace with current and emerging challenges, from weather- and climate-proofing military bases, to reducing fossil fuel dependence and shifting to renewable and low- and zero-carbon energy sources.

Alongside the demonstrated impact on the climate, fossil fuel use has led to a high level of energy and geostrategic dependence on a few resource-rich states that supply the majority of oil and gas globally. In 2021, the U.S., Saudi Arabia, and Russia produced 42 percent of the world’s oil, while the top 10 oil-producing nations were responsible for 72 percent of the global supply. Such dependence on imported oil and gas has long been exacerbating geopolitical competition, with the escalating global tensions and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine prompting a reassessment of energy security strategy for many states, with keener focus on links to the energy transition. The need to develop reliable and diversified energy supplies, and to onshore energy production where possible, is a challenge shared across both the national security and climate adaptation policy agendas. Success on both sides could be achievable through greater collaboration and resource-sharing if common goals and mutual interests can be articulated and translated into viable investment plans. Within a growing portfolio of policies and strategies to strengthen energy security and transition away from fossil fuel usage, diversifying energy sources with a strong focus on electrification as well as low- and zero-carbon high-density fuels provides an opportunity to simultaneously strengthen national defense and decarbonize national militaries, which are responsible for some of the largest carbon footprints in the world.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made energy security a national security priority

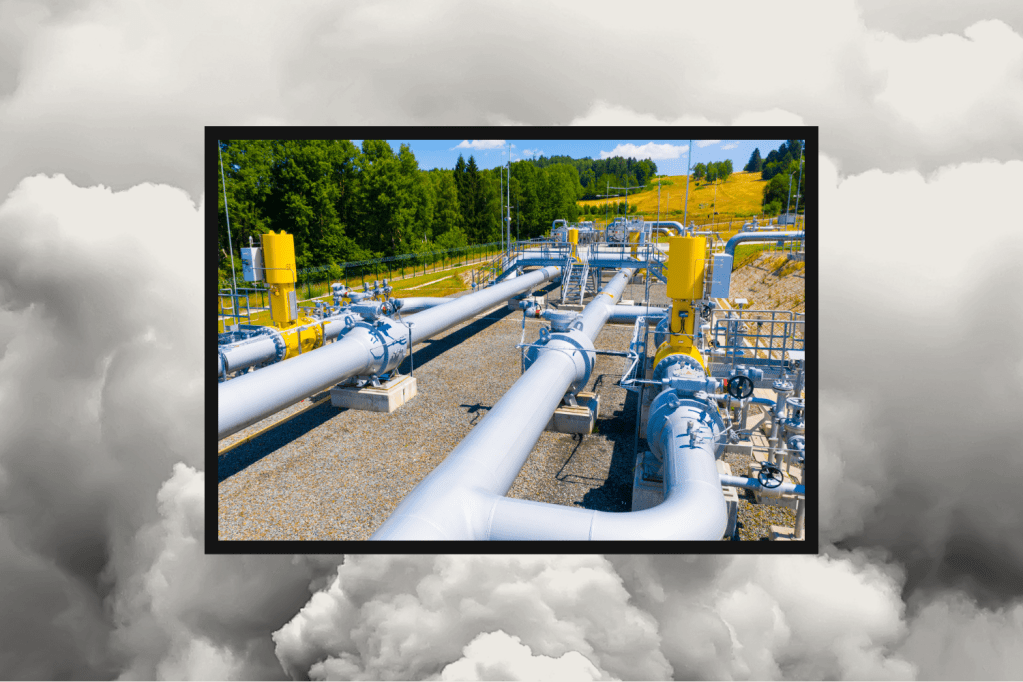

Acute energy security concerns and the clear risks of overreliance on a small number of foreign fuel and energy suppliers have come into sharpened focus since Russia’s February 2022 full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Among the world’s top exporters of crude oil and natural gas, Russia’s extensive and well-developed network of pipelines has enabled it to capture significant shares of Europe’s and Asia’s energy market. According to Eurostat, the European Union’s statistics’ office, in 2021 the European Union (EU) received the majority of its crude oil, natural gas, and coal from Russia. Russian fossil fuels made up nearly 30 percent of crude oil imports, 45 percent of natural gas imports, and over 50 percent of coal imports into the EU. Although Russia has over 12 pipelines that deliver gas to Europe, some of the most prominent include Russian-state owned company Gazprom’s Nord Stream pipelines or the Yamal LNG pipeline that stretches through Ukraine, and for which Russia continues to pay high transportation fees, despite the ongoing conflict.

While not currently a world-leading energy supplier, Ukraine is also home to significant liquified natural gas (LNG), coal, and oil reserves. These resources are mostly found in the eastern and southeastern regions that have been targeted by Russia since the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and under the Ukrainian Black Sea territory. These territories account for around half of Ukraine’s known oil, 72 percent of its natural gas, and almost all of its coal reserves and production. Additionally, Ukraine is home to deposits of 117 of the world’s most commonly used minerals, including titanium, iron ore, and untapped lithium, most of which are concentrated in areas under threat or occupied by Russia, including Zaporizhzhia, where Europe’s largest nuclear power plant is located. These resources promise to be critical to Ukraine’s economic development and competitiveness, particularly as countries around the world seek to secure access to the critical minerals that are vital to the energy transition and other advanced technology industries. Global demand for lithium, for example, is projected to increase by up to forty times in the coming decades as a result of the push toward green energy transition.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has become a contributor to climate change itself. Over the course of the first seven months of the war, military confrontation contributed to the release of an estimated 100 million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere. The as-yet unattributed attacks on the Nord Stream pipelines in September 2022 caused the biggest-ever single source release of methane. As the war continues, such environmental degradation is likely to be compounded by short-term efforts by countries to shore up energy supplies. Many countries—whether scrambling to close gaps caused by divestment from Russian energy suppliers or using cheaper fuels as a result of global energy market fluctuations—are turning to coal and LNG, both of which have larger carbon footprints than piped gas. Inside Ukraine, around 90 percent of wind power and 50 percent of solar power have been taken off-line since the start of the war, leading to greater reliance on non-renewable sources. Other major consuming countries, notably those in Asia, have increased their use of Russian energy. India has repeatedly signaled its interest and intent in expanding its economic engagement with Russia, which remains the source of around 85 percent of Indian oil imports. China’s Russian energy imports have increased by more than half since the beginning of the war, underscoring energy’s continued impact on geopolitical alliances.

Energy procurement and trade relations caused delays in the EU’s diplomatic response to the Russian invasion

Russia’s position as a key supplier of energy to Europe has diplomatic implications, impacting the speed and severity of global and regional response to the full-scale invasion of, and ongoing war in, Ukraine. Germany, for example, as the largest economy in Europe, both holds a powerful position within EU politics and governance and depends heavily on Russia for its fossil fuel needs, in particular natural gas.

Policy choices made by West Germany during the Cold War have contributed to the country’s current energy dependence on Russia. These policies, called Ostpolitik or “Eastern politics,” pushed West Germany to pursue closer economic relationships with Eastern Bloc states, including East Germany and the Soviet Union. As a result, by the end of the Cold War, Russia supplied the largest share of Germany’s natural gas—around one third of total imports—which helped fuel Germany’s manufacturing industry. Germany’s subsequent plan to phase out coal mining, enacted under Chancellor Merkel, pushed the country to invest further in LNG partnerships and pipelines with Russia. The Nord Stream I pipeline, which opened in 2011, and the Nord Stream II pipeline, which opened in early 2022, allowed Russia to send gas directly to Germany. These pipelines, which were heavily criticized by the U.S., the European Union, and Ukraine, are central to Germany’s dependence on Russian energy sources. Notably, in 2021 Germany received 34 percent of its crude oil, 66 percent of its natural gas, and 50 percent of its solid fossil fuels, including coal, from Russia.

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Germany’s energy relationship with Russia seemed poised to complicate or block the economic and diplomatic responses put forth by the EU and other allies. In late February 2022, for example, Germany initially opposed plans to cut Russia out of the SWIFT banking system—the conduit for German payments for Russian gas and raw materials—and successfully negotiated the omission of a ban on Russian gas imports from the first round of sanctions announced by the EU. While Germany later reversed its position on both subjects, this early dissent created uncertainty over the swiftness and solidarity of the international diplomatic response to the invasion.

Today, more than a year after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Germany has shifted its energy transition and supply strategies, reflecting the deteriorating relationship with Russia. The German government reopened 20 coal power plants last year to boost electricity supplies despite coal usage being in direct contrast with the country’s energy transition. Additionally, despite the prevailing negative public sentiment toward nuclear power, the German government announced plans to delay the wind-down of the country’s remaining nuclear power plants by several months and keep the three plants running until April 2023. Nuclear power from those plants currently provides around 5 percent of Germany’s electricity. While a small fraction of the national energy supply, this choice demonstrates some of the complicated choices Germany has been faced with in the wake of the Russian invasion.

Germany has also sought to diversify its energy suppliers. The German government has signed two medium-term contracts for LNG supply with companies based in Qatar and the United States that will secure 2 million tonnes of natural gas per year from 2026. Plans to construct a hydrogen pipeline from Norway were also announced in late 2022, which, alongside increased cooperation on climate and energy with other EU member states, such as Portugal and Poland, signals an intent to accelerate Germany’s green transition.

Looking Ahead: Bolstering security by investing in energy transition

The events of the past year have exposed the challenge of ongoing and disproportionate reliance on high-risk energy suppliers. In addition to Russia, other petro-states have, in recent years, experienced violence, political instability, and sanctions, undermining their ability to produce, process, and export fuel reliably. In addition, climate change itself, exacerbated by the burning of fossil fuels, is increasingly recognized as a driver of global instability by threatening livelihoods, inducing migration, precipitating or prolonging conflict, and contributing to political upheaval.

Long-term and deliberative planning will be necessary to shift from a fossil fuel-led energy strategy to one that prioritizes investments in local and regional low- and zero-carbon energy. Policymakers in Ukraine and the EU are responding to the devastating impacts of the war by designing and implementing long-term energy transition strategies, utilizing the opportunity presented by conflict-related shocks to the energy market, and attacks on energy infrastructure. In March 2023, for example, Ukraine’s Energy Minister German Galushchenko signed a memorandum of understanding with the EU to support energy transition as part of Ukraine’s reconstruction process, including supporting Ukraine to develop hydrogen and biomethane and creating an enabling environment for green energy investment. In addition, the EU’s REPowerEU plan lays out a short- and medium-term strategy for divestment from Russian fuels that prioritizes renewable energy sector development and investment, including in solar power. Beyond Ukraine, the EU is supporting energy diversification and transition in Asia. The bloc is also a contributor to the Just Energy Transition Partnership, agreed in December 2022, which will support Vietnam to meet its Net Zero 2050 goal through the mobilization of $15.5 billion to invest in renewable energy generation.

Moving forward, securing access to vital clean energy resources and investing in the manufacture of low- and zero-carbon components and supply chains can help to strengthen national and regional security. Furthermore, deepening strong diplomatic and trade relationships with resource-rich countries, utilizing foreign direct investment strategies that adhere to sustainable practices, and funding research to identify alternative sources and methods of developing and strengthening clean energy and carbon markets will be important strategic considerations.

Published: April 2023

By Isabel Schmidt, Senior Policy Analyst, FP Analytics, and Cara Skelly, Graduate Research Assistant, FP Analytics