Innovative Public Infrastructure for the Common Good

How purposeful design and partnerships can tackle real-world challenges and scale impact

An issue brief by FP Analytics, with support from Mastercard

August 2025

The global digital economy stands at a critical juncture as nations pursue increasingly divergent approaches to digital governance. From restrictions on cross-border data flows and localization requirements, to sovereign AI systems and industrial policies aimed at bolstering domestic digital champions, a complex web of frameworks is fragmenting the digital world. While these measures often reflect legitimate concerns about digital sovereignty, citizen privacy, and digital exclusion, they risk undermining the benefits of interconnected digital systems that currently power approximately $3 trillion in annual cross-border digital trade. This fragmentation stems from multiple forces: the return of great power politics, economic statecraft as a key instrument of national policy, the breakdown of traditional global order toward regional blocs, and COVID-19’s role as a major aggregator of how nation-states approach digital systems. The digitization of everything places a premium on data control, making the private sector’s role — alongside that of critical regulatory bodies and civil society — in developing common standards and interoperability increasingly vital.

As governments, intergovernmental organizations, and industry explore pathways to digital transformation, Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) is emerging as a foundational enabler. DPI provides promising frameworks for delivering essential digital services and expanding economic participation. However, there is no one-size-fits-all model. Early experiences, from India’s digital identity system to Estonia’s e-governance platform, highlight the complexity of aligning diverse priorities.

Rather than viewing these priorities as tradeoffs – such as accessibility versus security, or national control versus international compatibility – they can be approached as dimensions to be harmonized. Addressing this multifaceted landscape requires coordination, not compromise. Through thoughtful collaboration between public and private sectors, it is possible to design systems that are secure and inclusive, standardized yet adaptable, and locally governed while globally interoperable. Ultimately, national approaches to DPI must reflect local needs, including specific development goals, institutional capacities, and social contexts.

This issue brief examines how the public, private, and multilateral sectors can effectively collaborate to build innovative and inclusive digital systems that serve the public good. Drawing on best practices and lessons learned from multiple regions, it explores how DPI supports sustainable development, drives growth, and fits within broader digital governance frameworks, identifying approaches that can bridge digital divides while preserving the benefits of global connectivity.

The evolving global landscape of digital public infrastructure

Recent global gatherings demonstrate DPI’s growing prominence in development agendas, with national governments and multilateral institutions such as the World Bank and UN agencies eager to forge partnerships with industry to expand digital systems that serve the public good and support economic growth. For example, the Maceió Ministerial Declaration which emerged from the 2024 G20 summit in Brazil, explicitly calls for multistakeholder partnerships and stronger engagement with the private sector. It acknowledges that expanding well-designed digital systems and DPI can simultaneously advance multiple development goals — from financial inclusion to gender equality and more. This approach emphasizes universal access and shared benefits, challenging traditional models of digital infrastructure development.

At the same time, there is also growing international recognition among civil society stakeholders and development experts that poorly designed and implemented approaches to DPI can prove ineffectual while exacerbating existing inequalities. These inequalities manifest in multiple ways: digital ID systems that lack adequate alternatives for those with unreliable biometric data can restrict access to essential services for already marginalized populations; payment platforms that require smartphones may exclude low-income communities who rely on basic feature phones; and digital service portals that demand high levels of digital literacy can create new barriers for elderly, rural, and less-educated populations. The digital divide can deepen when DPI solutions prioritize efficiency over accessibility, or when they fail to account for offline alternatives for those who cannot access digital systems. Moreover, there are critical questions about governance, sustainability, and the balance between public and private interests that need to be carefully considered and addressed to ensure that ongoing and future DPI initiatives are inclusive and resilient. After all, the expansion of DPI represents much more than an ambitious technical project; it also represents a fundamental reshaping of how societies organize essential services.

DPI Maturity Across OECD Countries

Six key dimensions highlighting technological readiness and policy developments demonstrate varied progress on DPI adoption.

DATA SOURCE: OECD digital government index

Emerging regional models and their development impacts

Regional variations in digital readiness, cybersecurity vulnerabilities, and market structure all affect how DPI initiatives unfold in practice. Low and lower-middle income countries, especially across the global south, confront distinct challenges in balancing rapid digital transformation with institutional capacity and resource constraints. Overcoming these challenges will require concerted and coordination efforts across sectors that harness the skills and strengths of diverse stakeholders.

The relationship between DPI and sustainable development is becoming increasingly clear, though important questions about implementation and impact remain. Evidence from various regions suggests that DPI can advance multiple development goals simultaneously, including for example to drive financial inclusion and advance gender equality.

Recent analysis indicates that DPI’s impact on gender equality extends beyond simple access to digital tools. When designed thoughtfully, these systems can help address structural barriers that women face in accessing financial services and economic opportunities. Mobile banking initiatives in several countries, including Ghana’s mobile money interoperability system, have demonstrated how digital platforms can enhance women’s economic agency by increasing their purchasing power and productivity while improving household financial management.

The integration of DPI into national development frameworks marks a significant shift in how countries approach digital transformation. Rather than treating digital systems as standalone technical projects, more governments are embedding them within broader development strategies. This evolution reflects growing recognition that digital infrastructure can play a fundamental role in facilitating modern governance and enabling economic participation.

Furthermore, as highlighted during high-level discussions held on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum (WEF) Annual Meeting in early 2025, regional bodies like ASEAN, GCC, and APEC are becoming increasingly important venues for establishing digital frameworks and standards. This shift requires private sector and other stakeholders’ leadership in engaging across these venues to promote consistent approaches to interoperability and consumer protection. Equally important is ensuring that DPI systems are designed with a strong user focus – prioritizing accessibility, transparency, and accountability – so that digital infrastructure truly serves the needs and rights of individuals, as emphasized by Consumers International.

The evolution of DPI across different regions reveals both the adaptability and complexity of these systems in varying contexts. While early adopters have established influential models, emerging implementations underscore the need for tailored, contextually relevant approaches. A closer examination of national and regional experiences offers insights into both opportunities and challenges.

Illustrative National Case Studies on DPI

DPI typically encompasses foundational digital systems and databases, including digital identification, payment infrastructure, and data exchange platforms, that enable essential societal functions. The following examples illustrate both core DPI implementations and how these systems integrate with broader digital transformation initiatives, demonstrating that successful DPI provides the foundation upon which more advanced digital services and capabilities can be built.

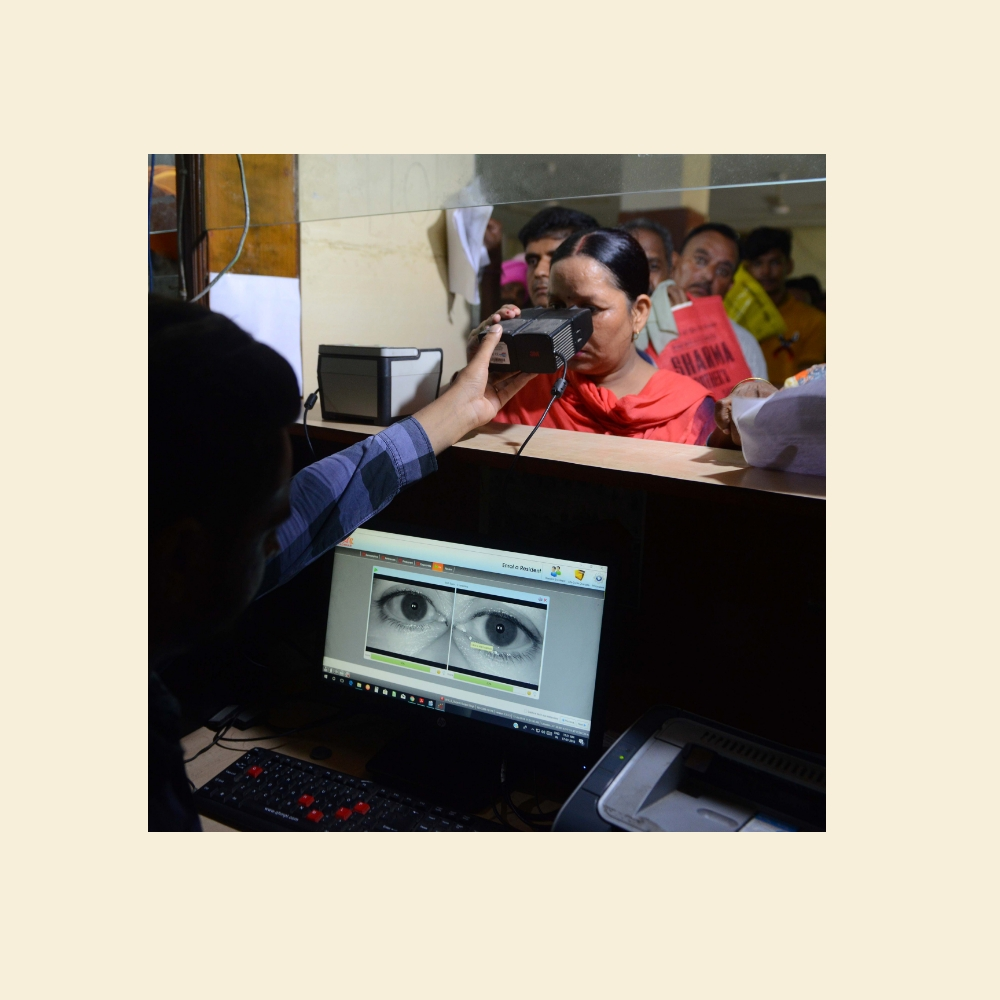

India

India’s experience with digital identity illustrates both the promise and challenges of large-scale DPI deployment. The Aadhaar biometric identification system, established in 2009, reaches over 1.2 billion citizens, representing an unprecedented achievement in digital identification. In practice, Aadhaar enables citizens to access a range of essential services, including subsidized food through the Public Distribution System (PDS), public healthcare benefits, and government welfare schemes like direct cash transfers to bank accounts. By linking identity verification with service delivery, the system has significantly reduced “benefit leakage,” a term referring to the diversion of resources due to fraud or inefficiency. For example, Aadhaar has ensured that welfare payments are received directly by intended beneficiaries, bypassing middlemen and reducing corruption. Concerns about exclusion persist, as individuals lacking reliable biometric data, such as manual laborers with worn fingerprints, sometimes face difficulties accessing their entitlements.

Photo: An Indian woman looks through an optical biometric reader during registration for Aadhaar cards in Amritsar, India.

Estonia

Estonia’s journey offers contrasting insights about building resilient digital systems in smaller nations. Following devastating cyberattacks in 2007, the country’s response through X-Road and the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE) demonstrated how a crisis can catalyze innovation. Estonia’s X-Road platform showcases how interoperable systems can transform public service delivery, such as enabling citizens to access healthcare, file taxes, or vote securely online. The X-Road platform’s emphasis on secure data exchange and privacy protection has influenced digital governance frameworks worldwide. For example, Finland adopted Estonia’s X-Road model to create its own secure data exchange system, enabling cross-border interoperability between the two countries. Similarly, Japan has drawn inspiration from X-Road to modernize its digital infrastructure, particularly in data-sharing across government agencies. However, replicating this success in different contexts is made challenging by factors such as varying levels of technical readiness, differing regulatory environments, and the absence of a robust cybersecurity architecture in many countries.

Photo: The logo of the NATO Cyber Range CR14 center in Tallinn, Estonia.

Singapore

Singapore’s “smart nation” approach highlights how core DPI components can be integrated into broader urban development strategies. The country’s digital identity systems and its public sector technology stack form the foundation of its digital infrastructure. By building on this DPI foundation and linking digital identity systems with healthcare, education, and urban planning, Singapore has addressed challenges such as resource management and public safety, for example, using drones to identify dengue hotspots challenges. Singapore’s success is difficult to replicate, as it is a wealthy city-state with a small, centralized population. Best practices, such as regulatory collaboration and knowledge-sharing through initiatives like the ASEAN Smart Cities Network, offer pathways for adaptation in less-resourced environments and among larger, more dispersed populations.

Photo: Teachers and students walk across the bridge at Marina Bay in Singapore.

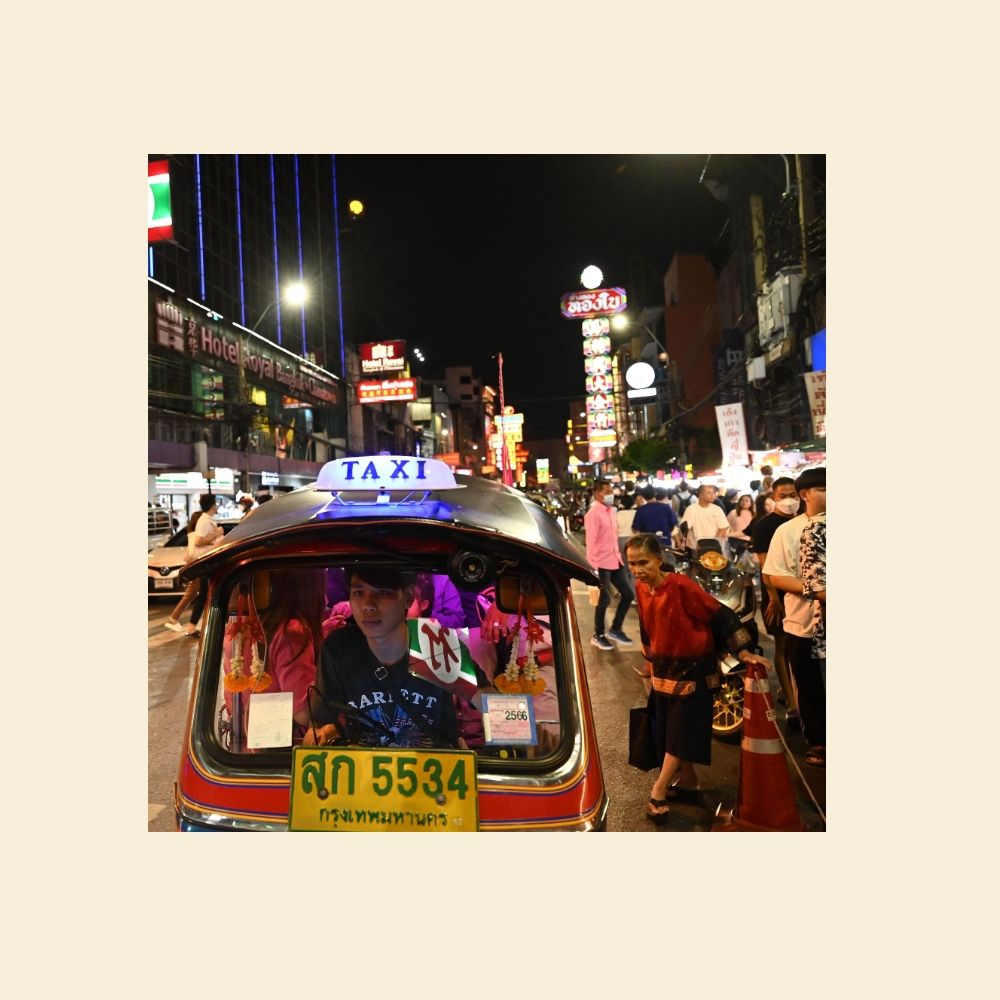

Thailand

Thailand’s digital finance strategy has positioned PromptPay as a cornerstone of its inclusive digital transformation efforts. Launched under the National e-Payment Master Plan, PromptPay enables individuals and businesses to send and receive money instantly using simple identifiers. This system has dramatically expanded access to digital payments, especially for small merchants and informal workers, by reducing transaction costs and eliminating the need for traditional banking infrastructure. The Thai government has emphasized PromptPay’s role not only in improving financial inclusion but also in enhancing the delivery of public services – such as tax refunds and welfare payments – through direct digital transfers. By integrating digital identity and payment systems, Thailand is building a DPI foundation that supports economic opportunity, fosters trust in digital services, and strengthens the resilience of its financial ecosystem.

Photo: An informal worker drives a tuktuk down a street crowded with tourists and other shoppers in Bangkok.

South Africa

South Africa’s digital initiatives are also aiming to address challenges like financial exclusion and unemployment. The introduction of digital credit platforms and mobile payment systems have created new opportunities for small businesses and rural communities and facilitated growth in e-commerce more broadly. Additionally, the government’s focus on interoperability aims to streamline service delivery and enhance public sector efficiency that can enable economic opportunity across the country and regionally. The government continues to prioritize these efforts as part of South Africa’s Digital Economy Mission Plan (DEMP), a broad-based effort tied to the National Development Plan to improve digital infrastructure, skills, innovation, digital commerce, and strengthen industry competitiveness. These initiatives position South Africa as a rising regional leader in leveraging DPI for sustainable development. Recent policy emphasis, including in the 2025 State of the Nation Address, underscores the role of digital identity and integrated government services as foundational tools to unlock economic opportunity and improve citizen access to essential services.

Photo: Participants play games at Africa Games Week, an event to bringing together game developers, companies, consumers and enthusiasts together in Cape Town, South Africa.

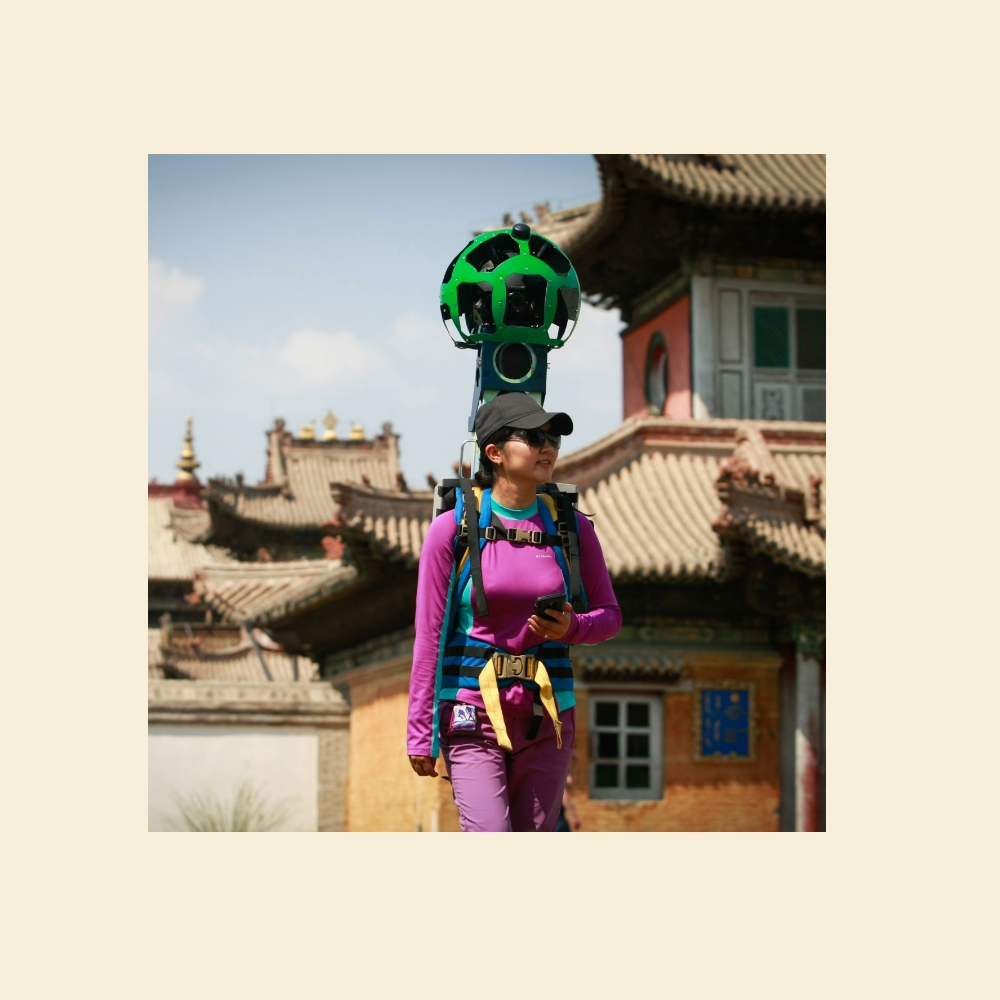

Mongolia

Mongolia offers an instructive case of how foundational DPI success can enable more advanced digital initiatives in a challenging context. The country built robust digital payment infrastructure first, achieving 95% digital banking penetration with approximately 98% of transactions conducted online despite a population of just 3 million spread across vast geography. Building on this DPI foundation, Mongolia is now addressing emerging technological divides through initiatives like the AI Academy, which teaches practical AI skills to farmers, herders, and disadvantaged communities. According to experts convened to discuss DPI at WEF, Mongolia’s comprehensive approach — first establishing core digital infrastructure and then building advanced services and skills development on top of it — demonstrates how countries can bridge traditional digital gaps while simultaneously preparing populations for emerging technologies like AI, ensuring digital inclusion evolves with technological advancement.

Photo: A Google Street View worker walks with a specialized camera to record the surroundings in the Mongolian capital of Ulaanbaatar.

Specifically, there are many other cases of DPI’s impact as an effective financial tool. In Poland, for instance, the integration of digital payment systems with small merchant networks has dramatically expanded access to financial services in underserved regions, while Romania’s experience with mobile banking illustrates how digital solutions can reach previously excluded populations. Similarly, in Bangladesh, the combination of microcredit and mobile technology, such as the use of platforms like bKash, has enabled millions of unbanked individuals, particularly women, to access financial services, start small businesses, and achieve greater economic independence.

While these examples illustrate successful DPI implementations, the global landscape includes many other instructive cases that reveal both promise and complexity. From Ghana’s digital address system that revolutionized location services despite connectivity challenges to Ukraine’s Diia platform developed amidst conflict, these diverse experiences demonstrate that DPI implementation is highly context-dependent. Rwanda’s rapid digital transformation efforts, Peru’s attempts to digitize public services, and Vietnam’s ambitious national digital transformation strategy further highlight how countries at various development stages are navigating the technical, social, and institutional challenges of building digital infrastructure. These varied journeys remind us that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to DPI, and that thoughtful adaptation to local conditions remains essential for success.

Risks and opportunities in DPI adoption and implementation

The growing centrality of DPI in public economic and social systems brings with it a complex set of considerations that warrant careful examination. While DPI promises transformative benefits, recent experiences highlight challenges in implementation, security, interoperability, and governance that could undermine its effectiveness or even exacerbate existing inequalities. These challenges are particularly acute as countries simultaneously navigate broader digital economy trends, including the rapid emergence of AI systems, increasingly complex cybersecurity threats, evolving digital trade frameworks, and growing concerns about data sovereignty.

Core tensions in DPI development

Digital fragmentation represents a fundamental tension in DPI development. As countries pursue independent digital strategies, incompatible systems and divergent standards threaten to create new barriers in our interconnected world. The emergence of what some observers call the “balkanization of cyberspace” raises concerns about the future of cross-border services and international cooperation. This fragmentation could particularly impact developing economies that rely on international digital trade and services.

Sovereignty considerations add another layer of complexity to effective and inclusive digital transformations that serve the public good. Nations increasingly seek to maintain control over their digital infrastructure, viewing it as critical to national security and economic independence. However, this drive for digital sovereignty often conflicts with the need for global interoperability. Data localization requirements, for instance, while intended to protect citizen privacy and national security, can fragment global services and increase costs. However, some approaches to digital sovereignty, like protective measures, can lead to isolated digital ecosystems.

Market dynamics present additional challenges in DPI development. Public DPI initiatives can inadvertently distort markets, particularly in the financial sector where government-backed systems may compete with private services and potentially crowd out innovation. Promoting innovation through market forces is essential for developing cutting-edge, efficient solutions that evolve with technological advances. However, experience has demonstrated that market forces alone often leave significant segments of the population behind — low-income individuals without access to traditional banking, older adults who struggle with digital literacy, or minorities in underserved areas lacking internet infrastructure.

This is precisely where public-private partnerships become necessary and valuable. Such partnerships can combine the innovation and efficiency of private markets with public oversight and commitment to universal access. For instance, in some countries like Thailand, collaboration between government agencies, financial institutions, and technology companies has enabled the development of inclusive payment systems that serve both commercial interests and public policy objectives. These partnerships allow governments to address market failures while leveraging private sector expertise and investment capacity. Finding this carefully constructed, people-centered balance — one that reflects local market conditions and development objectives while ensuring no population segment is excluded — will be key to the success and sustainability of DPI efforts.

Critical implementation challenges

The human dimension of DPI implementation concerns the ways in which these systems directly impact individuals and communities, emphasizing user experiences, accessibility, and equitable outcomes. Many current systems struggle with user-centricity and accessibility, potentially excluding vulnerable populations, such as rural communities with limited internet access or marginalized groups like refugees and undocumented migrants who may lack the necessary documentation to use these systems. Privacy concerns are particularly acute, as centralized digital systems collect unprecedented amounts of personal data, raising questions about how that data could be misused or abused to persecute populations or exploit individuals.

While discussions of DPI often focus on software and services, the fundamental importance of physical infrastructure cannot be overlooked. Critical elements like submarine cables, data centers, and energy supplies create real constraints on digital transformation. The costs and complexities of maintaining this physical layer — from managing energy prices for data centers to ensuring redundancy in submarine cable systems — merit careful consideration in DPI planning.

Cybersecurity vulnerabilities become more critical as societies grow increasingly dependent on DPI. The fourfold spike in attacks on Finland since 2023 demonstrates how hostile actors can target DPI. And ransomware incidents targeting essential services, such as the 2021 Colonial Pipeline Attack, reveal the evolving sophistication of these threats.

These risks are particularly acute for smaller nations and developing economies that may lack robust cyber defense capabilities, underscoring the need for governments and industry to work together to prioritize cyber security and strengthen the resilience of digital systems in order to protect citizens and minimize disruptive or destructive impacts. Industry leaders emphasize that the increasing costs of cybersecurity present a particular challenge for private sector investment and innovation. As companies face complex regulatory requirements across different jurisdictions, the expense of maintaining robust security measures while ensuring compliance can potentially limit market entry and competition, especially for smaller players and startups.

As DPI systems scale and evolve, questions of their long-term sustainability and resilience become paramount. The challenge extends beyond technical robustness to include institutional capacity, such as the ability of governments to manage and maintain complex systems, ensure adequate funding, and build the necessary human expertise to operate and secure DPI effectively. Recent experiences in Southeast Asia highlight how varying levels of digital readiness can affect regional integration efforts and system resilience. While Singapore excels in digital workforce readiness and technical capacity to maintain sophisticated systems, other ASEAN members like Indonesia and the Philippines face significant gaps in STEM education and digital talent development, which hinder their ability to effectively operate and sustain complex digital infrastructure over time. This disparity in technical capacity creates fundamental challenges for reliable system operations across the region, with interoperability becoming a secondary concern when basic maintenance and security management remain difficult.

Opportunities for transformative impact

The economic benefits of DPI extend far beyond individual services to influence broader market dynamics. By reducing administrative barriers and streamlining processes, well-designed DPI can enable new forms of entrepreneurship and innovation, particularly in developing economies. Small enterprises can thrive through simplified registration systems and improved access to formal markets. Tailoring these solutions to local contexts can help ensure that both urban and rural communities benefit.

The role of software platforms in expanding digital access offers promising opportunities for inclusive growth. For example, industry platforms that combine business management tools with payment capabilities can help bring informal sector workers into the digital economy. When manual service providers like pool cleaners or gardeners can gain access to digital scheduling and payment systems, they often see improved working capital management and better access to formal financial services. This ‘platformization’ of commerce, as noted by leaders convened alongside WEF, represents an important pathway for expanding digital inclusion, particularly for small and medium-sized enterprises.

Perhaps most significantly, DPI opens the door to innovative public-private collaboration in service delivery. Traditional models often forced a choice between public provision and market solutions. However, digital infrastructure enables hybrid approaches that combine private sector creativity with public oversight, resulting in efficient, inclusive solutions for essential services. Designing governance frameworks that balance these interests effectively will be key to unlocking this potential.

Additionally, the development of DPI spurs advancements in cybersecurity and privacy protection, innovations that can strengthen digital systems across sectors. Investments in safeguarding critical digital infrastructure are not just about mitigating risks; they also create opportunities for seamless, secure data exchange that enhances service delivery and economic efficiency. Countries that prioritize thoughtful system design and governance frameworks can set benchmarks for balancing privacy, security, and national sovereignty while maximizing the opportunities presented by DPI.

Digital Governance and Political Participation Trends, 2016-2024

Across high- and middle-income countries, e-participation and e-governance have varied over time.

DATA SOURCE: world bank

These challenges underscore the need for thoughtful approaches that consider local contexts while maintaining global compatibility. As more countries deploy DPI systems, understanding and addressing these kinds of risks will be crucial for realizing the potential benefits while avoiding unintended consequences. Continued experimentation and learning across different contexts will also be critical, with careful attention to both immediate impacts and long-term implications of digital systems for social and economic development. With the right strategies, countries can harness the full potential of digital infrastructure and pave the way for inclusive development pathways that foster entrepreneurship, innovation, and broader economic growth.

The importance of cross-sector coordination and leveraging stakeholders’ expertise

Achieving success with DPI requires coordinated action across multiple sectors, with each group playing distinct but complementary roles to address specific challenges that markets alone cannot solve. While market-driven innovation is essential, experience has consistently shown that certain population segments get left behind without intentional intervention. This reality makes public-private partnerships not just beneficial but necessary for truly inclusive digital infrastructure.

Government institutions can identify market failures, create enabling regulatory environments, ensure equitable access while protecting public interests, invest in foundational digital infrastructure where commercial incentives are insufficient, and foster international cooperation. The private sector brings critical technical innovations, operational expertise, infrastructure investment capabilities, and the ability to create value-added services that respond to specific user needs. Moreover, philanthropic organizations have emerged as important catalysts for DPI development, particularly in resource-constrained environments. Meanwhile, multilateral institutions can facilitate international collaboration, offer technical assistance, develop common standards, and promote the exchange of best practices to strengthen global digital governance.

Industry stakeholders emphasize that effective coordination requires concrete action steps focused on solving specific problems rather than diffuse efforts across multiple priorities or creating solutions in search of problems. Success stories like M-PESA in Kenya demonstrate how problem-focused collaboration between mobile operators, banks, and development partners addressed a specific challenge — lack of financial access — dramatically increasing banking inclusion from 10% to over 40% of the population. Similarly, the UK’s experience with real-time payments infrastructure shows how strategic private sector investment can help establish effective standards that solve specific payment friction problems.

The most successful partnerships recognize that DPI isn’t a one-size-fits-all proposition. Solutions must be tailored to address the specific challenges, resources, and priorities of each context. What works in Singapore may not work in South Africa, not because one approach is superior, but because the problems being solved and the constraints being navigated are fundamentally different. Effective cross-sector coordination involves careful assessment of local needs, capabilities, and barriers before determining which DPI elements will deliver the most immediate value, and which stakeholders are best positioned to address specific gaps in the digital ecosystem.

Building inclusive digital architectures

Creating truly inclusive digital systems requires rethinking traditional infrastructure models. Effective DPI design must prioritize accessibility, user-centricity, and adaptability to local contexts – especially in developing economies where digital literacy and infrastructure gaps persist. The dynamic between protecting national digital sovereignty and fostering global connectivity does not represent a significant barrier for responsible DPI development. The European Union’s experience with GDPR demonstrates how enacting new regulatory frameworks can strengthen citizen privacy while enabling cross-border data flows.

Several promising models have emerged across various regional blocs. These include the ASEAN Data Management Framework, the Nordic-Baltic eID (NOBID) project, and the World Bank’s West Africa Unique Identification for Regional Integration and Inclusion (WURI), among others. Shared, noteworthy features among these initiatives are:

- Regional data-sharing agreements that uphold privacy while fostering innovation

- Technical standards that support interoperability and national autonomy

- Cross-border digital identity systems that facilitate trade and mobility

- Industry-led frameworks for payments and authentication across jurisdictions

- Multilateral cybersecurity cooperation that accounts for institutional diversity

Strengthening international coordination

As DPI becomes central to digital governance, international coordination is essential. The G20’s growing focus on DPI presents an opportunity to align efforts across borders. Priority areas include:

- Developing shared technical and regulatory standards

- Coordinating cybersecurity strategies

- Supporting DPI initiatives in developing countries

- Promoting co-governance models that balance public oversight with private innovation

The OECD’s recent policy brief reinforces this direction, defining DPI as “shared digital systems that are secure and interoperable,” and emphasizing safeguards against exclusion and system fragility.

Operationalizing DPI: governance, trust, and sustainability

Long-term DPI success depends on robust governance and sustainable funding. In this context, public-private partnerships offer a powerful mechanism for scaling innovation, sharing risk, and ensuring operational resilience. When thoughtfully structured, public-private partnerships can help align incentives, mobilize expertise, and deliver inclusive outcomes, when structured to:

- Maintain a focus on public benefit while enabling innovation

- Ensure equitable access and commercial viability

- Build local capacity and leverage global expertise

- Address both immediate needs and long-term resilience

Trust is foundational. It requires transparency, citizen engagement, and early wins that demonstrate value. Clear, long-term funding strategies are also critical to ensure that initial investments evolve into durable, adaptable systems.

Looking Ahead

As digital systems become central to economic and social life, DPI offers both a powerful opportunity and a pressing imperative. Experiences across regions show that success hinges not on choosing between public or private approaches, but on designing systems that combine the strengths of both.

The most effective DPI models are built on a clear foundation: governments provide core infrastructure while enabling private sector innovation to flourish around it. This balance can ensure universal access, security, and resilience, while unlocking value-added services and inclusive growth.

But infrastructure alone is not enough. DPI must be designed with people at the center – solving real problems, protecting rights, and earning trust. That means demonstrating tangible benefits to users, ensuring transparency, and embedding flexibility to evolve with changing needs.

To realize DPI’s full potential, governments must avoid over-engineering, define minimal viable standards, and foster open, interoperable ecosystems. The private sector, in turn, must embrace shared infrastructure and co-governance models that expand markets and reduce long-term costs.

The path forward requires sustained collaboration across borders and sectors – anchored in a shared commitment to inclusion, accessibility, and equity. The success of DPI will be measured not by its complexity, but by its ability to empower people and drive sustainable development.

By Alex Leader (Affiliate Researcher) and Allison Carlson (Executive Vice President, FP Analytics & FP Events). Art direction and design by Sara Stewart. Illustration by Christian Gralingen for FP Analytics, photos from Getty Images.

This issue brief was produced by FP Analytics, the independent research division of The FP Group, with support from Mastercard. FP Analytics retained control of the research direction and findings of this issue brief. Foreign Policy’s editorial team was not involved in the creation of this content.