Seizing Opportunity at the Climate-Health Nexus

Key actions to minimize climate change’s impacts on global health

An issue brief by FP Analytics, produced with support from Viatris.

MAY 2025

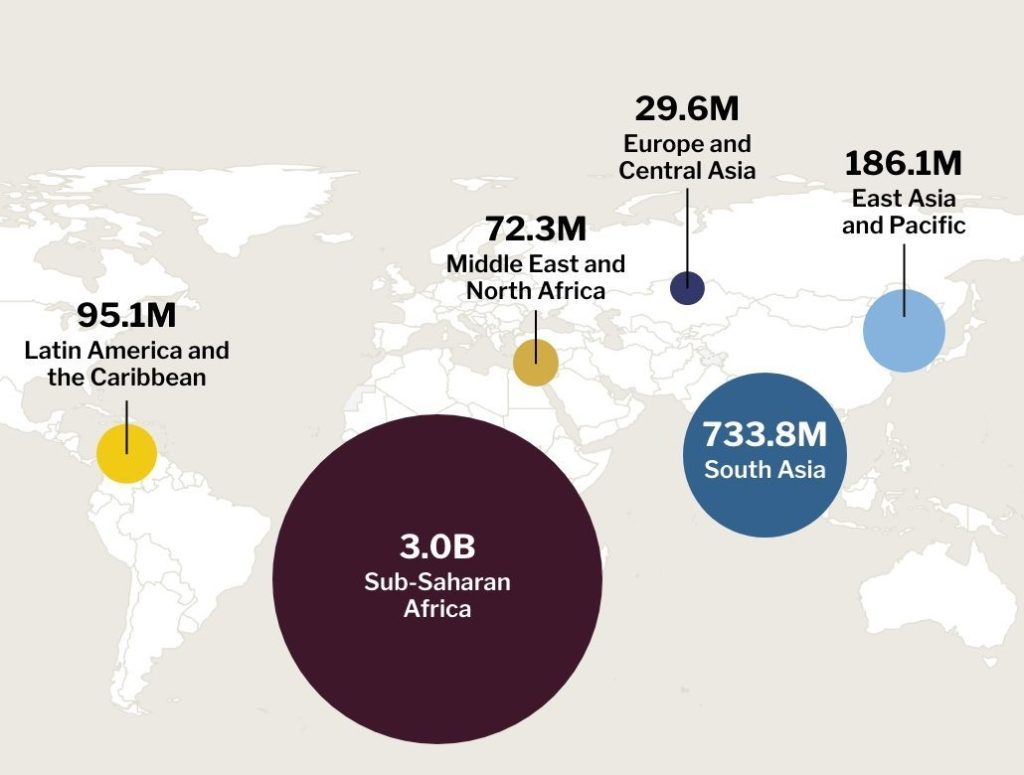

After 2024 became the first year in which global warming rose above the 1.5°C threshold, the impacts of climate change on public health have come into sharpened focus. Rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns contribute to a myriad of negative health outcomes. These include increased incidence and mortality from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), growing mental health burdens, the proliferation of infectious diseases, increased prevalence of antimicrobial resistance, and disruptions to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) systems, among others. Rapid-onset extreme weather events, exacerbated and made more frequent by climate change, pose a major threat, placing communities at acute risk from wildfires, floods, heat waves, and other phenomena. Such events also destabilize the day-to-day functioning of health systems, stretching finite resources and leading to disrupted or foregone medical care. While climate change’s impacts are being felt across wealthy and developing states alike, lower-income countries and communities are most at risk, as populations and health systems in these contexts remain both the least prepared and least resourced.

With health, as in other sectors, climate change represents a borderless challenge that calls for multistakeholder and collaborative international action. Manifestations of climate change, like rising ambient temperatures, droughts, and sea-level rise, threaten health and well-being across entire regions, even entire hemispheres, in broad strokes. One estimate predicts that the planet’s current climate change trajectory will lead to an extra 14.5 million deaths and USD 12.5 trillion in economic damages due to illness by 2050. The immense human and economic costs posed by these shifts demand policy action, cooperation, and investment by local and national governments, health care companies and providers, international financial institutions, and civil society organizations. Beyond responding to acute crises, concerted actions are needed to address the underlying vulnerabilities and contributing factors that stymie health care access and threaten health care systems. As the global community prepares for the historic convening of the 30th Conference of Parties (COP30) in 2025 in Brazil, it is imperative for stakeholders in global health and climate change to come together to accelerate investments and scale up innovative actions to make health care climate responsive and climate resilient. This issue brief identifies promising and targeted interventions to address, adapt to, and mitigate the health impacts of climate change and drivers of inequity around the world. Recognizing the enormous challenges at the climate-health nexus, the brief critically examines key levers for action, including health system strengthening, leveraging technological innovation, building an enabling policy environment, and bolstering sustainable climate finance mechanisms.

PART 1

Understanding global progress toward climate goals and actions to-date

Health-related climate mitigation and adaptation efforts demonstrate significant ambition but insufficient follow-through and investment.

Progress on climate adaptation and mitigation has been slow, uneven, and inadequate. Calling for a 60 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2035, the first-ever Global Stocktake—a summation of extant efforts and unaddressed gaps in the fight against climate change, published by the UN in 2023—warned of dire climate-driven health, water security, and other risks if this target goes unmet. The UN Environmental Programme’s Adaptation Gap Report 2024 likewise reiterates that far too little is being done to prepare the world to cope with climate change’s impacts, finding that the adaptation finance gap is “extremely large” and that climate-health action is underprioritized.

Efforts to address the policy and resource gaps at the climate-health nexus have been proliferating in recent years, starting with the first-ever COP Health Day, at COP28 in Dubai, which set the stage for the milestone Declaration on Climate and Health. Recognizing the inherent interdependence between the two issues, the non-binding agreement was signed by over 140 countries and accompanied by a USD 1 billion commitment. High-level actions followed at COP29, including the Baku COP Presidencies Continuity Coalition for Climate and Health, which solidifies the commitment of five recent or upcoming COP host countries—including Brazil—to prioritize health as a key component of ongoing and future climate change mitigation efforts. As of 2024, 95 percent of all countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) for fighting climate change mention health considerations, and one-third of NDCs allocate funds for action on health issues.

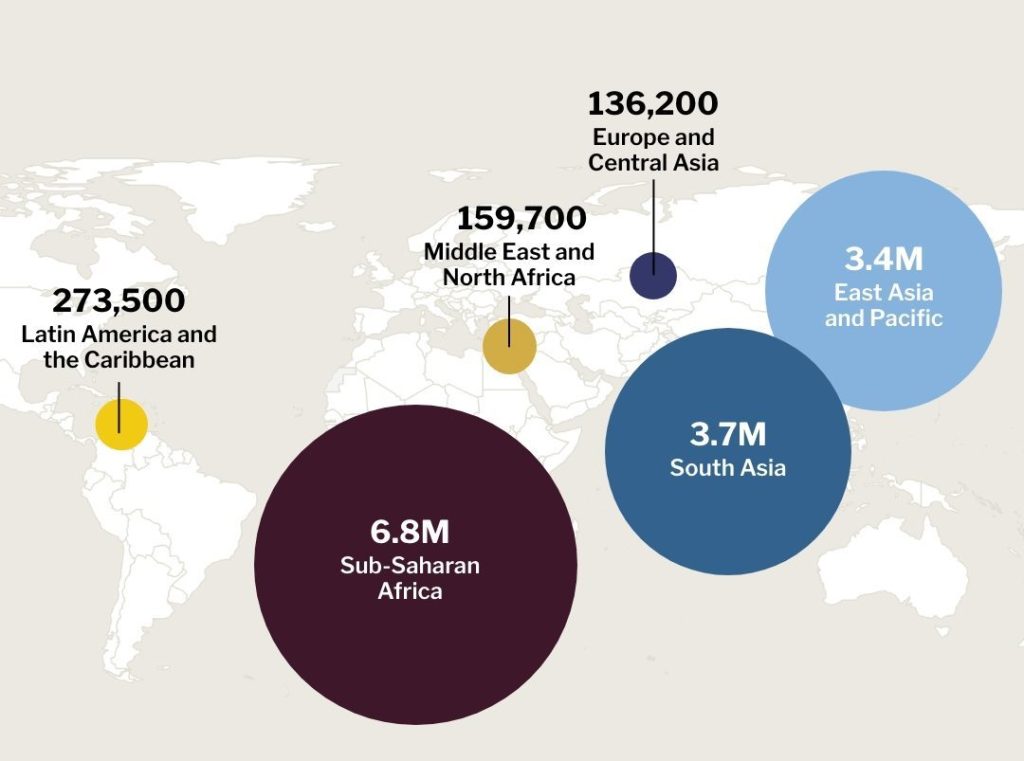

However, funding remains a critical point where action does not match ambition, in health system adaptation as well as climate mitigation and adaptation writ large. The Climate Policy Initiative estimates that climate finance flows in 2023 totaled roughly USD 1.5 trillion—still just one-fifth of the level needed to keep the 1.5°C threshold within reach by 2030. The vast majority of these funds are concentrated in mitigation efforts in the energy, transport, and buildings and infrastructure sectors. Health-related adaptation spending, on the other hand, accounts for just 0.5 percent of all multilateral climate spending and 2 percent of total adaptation spending. While such spending may be trending upward, it remains far from sufficient, with estimates of an overall climate-health adaptation shortfall of between USD 26 billion and USD 56 billion annually.

PART 2

Expanding and accelerating adaptation and mitigation strategies for climate-resilient health care

The threat climate change poses to global health warrants concerted action by stakeholders from across the public, private, and multilateral sectors. Action in four key areas—health system strengthening, technological innovation, enabling policy, and sustainable financing—should be prioritized to safeguard and expand communities’ access to health while building resiliency and prosperity worldwide.

1. Health system strengthening can prepare communities for climate-related health challenges and form the foundation for healthier, more productive lives.

Counteracting the health impacts of climate change depends on preparing systems for climate-driven health crises, improving the resiliency of health infrastructure, and supporting the broader foundations of good health against climate-health stressors. A high heat-mortality event that had a one-in-100 chance of occurring in the year 2000 now has a probability of occurring of less than one-in-20. To address this and other climate-sensitive health risks, health systems need to build adequate, context-informed health care capacity. Patients everywhere can benefit from climate-informed training for health care professionals to better detect and treat climate-related illnesses. For example, this could involve enhanced capacity for treating NCDs exacerbated by extreme heat, such as cardiovascular disease, or introducing targeted monitoring in flood-prone locations to mitigate rising risk from water-borne illnesses. A combination of efforts will be needed to adapt health care provision—at home, in clinics, and in hospitals—to meet climate change’s multidimensional impacts.

Climate change also presents a physical threat to health system infrastructure, for example, by damaging or destroying clinics and hospitals, disrupting electricity critical to life-saving care, and interrupting supply chains. Estimates suggest that by 2100, one in every 12 hospitals worldwide will be at high risk of total or partial shutdown due to extreme weather events. Resilient infrastructure is particularly important for crisis scenarios where hospitals may need to treat many patients at once, such as during the heat waves that struck Europe in 2022 and led to 61,000 deaths. Similarly, the disruption of medical supply chains can yield wide-reaching impacts. In 2024, Hurricane Helene shut down a manufacturing plant responsible for 60 percent of the United States’ supply of intravenous fluid (IV), leading to nationwide rationing and the delay of elective surgeries, even months after the storm hit.

Finally, health system adaptation and mitigation efforts also need to consider the broader foundations of good health, which depend on access to clean drinking water and nutritious food. Gradual or abrupt climate impacts can endanger access to clean water, threatening good sanitation and hygiene practices and hastening the spread of water-borne illness. Projects like the World Bank’s Global Water Security and Sanitation Partnership seek to secure the mutual benefits present in areas like water security and health, such as by integrating climate resiliency into wastewater and septage management in Indonesia. Similarly, climate-resilient agriculture and food security programming can secure substantial health benefits, as malnutrition is a key risk factor for many illnesses, and food access can be curtailed by climatic events such as droughts, flooding, and saltwater intrusion.

As stakeholders seek to build up health system resilience against climate change’s impacts, they must consider how many disparate aspects—from therapeutics to infrastructure to water and nutrition—combine to determine health outcomes and potential climate-driven risk. This will include integrating new technologies and therapeutics, which can help expand access to care.

2. Technological and therapeutic innovation can help mitigate climate change’s impacts on health care while improving access and treatment options.

Technological innovation holds promise to help counteract climate change’s impact on health and well-being, including through health care delivery, early warning, diagnostics and monitoring, and crisis mitigation. New medicines and delivery methods could enable access to treatment options for patients while improving the resiliency of health-related supply chains. A number of medications and treatments, such as vaccines, tend to be dependent on expensive, temperature-controlled supply chains, a challenging hurdle for delivering medications to remote contexts with fluctuating temperatures. As a result, products like heat-stable, longer-lasting vaccines can improve supplies and enable easier access. For example, Rotasiil, a rotavirus vaccine developed by the Serum Institute of India, is capable of bearing temperatures of 40°C (104°F) for up to 18 months. Climate resilient health care will depend on a broader global ecosystem that can deliver medications and care to those who need it most amid shifting, and even dangerous, climatic conditions.

A wide range of digital tools can also be leveraged to counteract climate change’s impact on health. The advent of digital technologies in everyday medical situations, such as telehealth applications and wearable devices, are enabling new ways for health systems to interact with patients, collect information, and encourage timely care. For example, climate change is a growing source of mental illnesses, like anxiety and depression, and telehealth applications hold promise to help patients receive access to consistent, practical mental health support, including in contexts of climate-related displacement. Data collection and monitoring systems can also help mitigate climate-related challenges to health. India’s Electronic Vaccine Intelligence Network (eVIN) features a cloud-based monitoring system that helps track vaccine stocks and temperatures across all of the country’s 733 districts in 36 states. The system is credited with reducing vaccine stock-outs by 80 percent and achieving a 99 percent vaccine availability across all of India’s cold chain points.

Cutting-edge technologies, from drones to artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML), likewise have a place in improving health care outcomes amid a changing climate. Data collection and early warning systems, such as the WHO Hub for Pandemic Intelligence, use AI/ML to more rapidly analyze vast swathes of data and uncover relationships that human analysts might miss. Technology like smart thermometers and geospatial intelligence from drones and satellites can be used in tandem to permit early warning and mitigation efforts to counteract climate change-driven disasters like droughts and cyclones. In one use case, cross-referencing topographical maps with rainfall totals and satellite imagery of vegetation coverage—including use of AI tools to aid data processing—can help identify communities at high risk to dangerous mudslides. As technology advances, policymakers can help ensure that these and other tools are in reach for practitioners in the field by building frameworks that enable access, disseminate best practices, and secure the resources needed for deployment at scale.

3. Climate-responsive policy frameworks are key to mobilizing health system adaptation and enabling the technology and resources critical to its success.

Wealthy and developing countries alike have much more to do to establish and right-size policy initiatives in the climate-health nexus, including by encouraging multilateral and cross-sectoral collaboration, and addressing synergies with adjacent policy priorities. At the country level, few states have meaningfully incorporated health into their National Action Plans (NAPs) or separately developed Health National Action Plans (HNAPs). According to a 2023 study, only 22 of 160 analyzed countries had an HNAP, and less than half of developing countries’ NAPs included a mention of health and well-being. Countries would benefit from addressing these policy gaps, building on quality criteria provided by the World Health Organization (WHO), which include comprehensive coverage of climate-sensitive health risks and rigorous monitoring, evaluation, and reporting. Furthermore, additional climate-relevant planning documents, such as Heat Action Plans, can support more targeted, effective policy intervention such as forestalling the worst impacts of extreme heat events.

Cross-border collaboration, commitment, and sharing of best practices are key to climate-proofing health care and strengthening health outcomes. Headline commitments like the Declaration on Climate and Health can be complemented by other climate-health fora and initiatives that bring countries together to address common problems. For example, the WHO’s Alliance for Transformative Action on Climate and Health (ATACH), emerging from COP26, helps drive technical discussion through working groups on finance, climate resilience, sustainability, supply chains, and nutrition. Similarly, it is both cost-efficient and logical to collaborate and share certain resources across borders to respond to acute climate-driven health crises. Such cooperation, embodied by efforts like the Global Outbreak Alert and Response System and Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction, not only improves relationships with neighbors and partners but is also in each contributing country’s direct interest, as highly destructive or long-lasting crises in a country’s neighborhood can lead to environmental, economic, and migration-related impacts at home. Given that 4.5 billion people—more than half of the global population—are at high risk of experiencing an extreme weather event, countries stand to benefit from enhanced cooperation to prepare for and mitigate climate change’s health-related impacts across a range of international mechanisms and fora.

Governmental, multilateral, and private-sector stakeholders also need to be cognizant of the importance of reaching all communities with health-related climate adaptation efforts, as well as the many levers for enacting change in this space. Vulnerable populations, such as low-income groups and refugees, tend to be the most at risk from climate change’s health impacts and start from the lowest baselines in terms of access to health care. The concerns of these communities can be addressed directly through policy, as Canada has done through its Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program, which directly funds efforts by First Nations and Inuit communities to respond to health impacts from climate change. Governments can better meet the needs of their constituents by integrating climate and health considerations across sectors whenever possible. In the case of the built environment, for example, prioritizing climate-resilient housing and infrastructure is not just about hardening systems against extreme weather events but also building housing that supports broader climate-health goals, like limiting indoor air pollution, reducing potential exposure to toxic substances, supporting mental health, and improving access to clean drinking water and sanitation. A holistic approach to climate adaptation can not only protect health but also improve quality of life, returning multifaceted benefits for every dollar spent.

4. The success of health-related climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts hinges on the world’s ability to mobilize and scale up sustainable financing mechanisms.

As with other sectors of climate finance, health-related adaptation and mitigation efforts are woefully underfunded. The annual climate-health adaptation finance gap, totaling as much as USD 56 billion, needs new resources and fresh thinking in order to be reduced or closed. Reconceptualizing spending on climate and health as self-amortizing investments with society-wide benefits and reiterating potential gains is key to shifting the conversation from spending that needs justification to spending that is nonsensical to forgo. The financial rationale for preventative action is similarly clear across sectors, such as through favorable return on investment for early-warning and monitoring systems in both climate and health. In one major example, a 30-year assessment of the Clean Air Act by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency estimates that its benefits—primarily through reduced premature mortality—exceeded 30 times the cost of compliance and implementation.

There are also areas of significant overlap among adjacent goals spanning climate, health, water and food security, and economic development where targeted investments can yield compounding benefits across multiple policy goals all at once. In a 2023 study, McKinsey identified USD 7 to 25 billion in high-impact investments that could simultaneously address health system strengthening and pandemic preparedness and response. This approach can be applied across the climate-health nexus to identify efficient investments, from low-carbon transportation solutions that reduce air pollution to climate-resilient housing that aids physical and mental health. In the case of climate-resilient agriculture, for example, the same well-targeted dollar can protect a community against climate change impacts, reduce threats to health, enhance food quality and access, and improve household income. To make the most of these opportunities, policymakers and researchers need to continue to collect data, share best practices, and pursue synergies between climate and health investment portfolios.

Stakeholders will need to pursue an “all-hands-on-deck” approach to climate finance and deploy established and novel funding arrangements mechanisms alike to close the gap. These tools will take many forms. Public-private partnerships are key to mobilizing cross-sectoral resources, like the InsuResilience Global Partnership. The organization features over 120 member entities, including country governments, private-sector companies, multilateral institutions, and civil society organizations, all working to develop climate and disaster risk finance and insurance solutions. Other climate risk efforts, such as the African Risk Capacity, demonstrate the ability to deploy modern tools like risk pooling and risk transfer to cost-efficiently help member countries cope with extreme climate events. Climate-health taxes, such as France’s General Tax on Polluting Activities, directly tax companies for harmful emissions and waste and then reinvest proceeds into climate- or health-focused programs. There are also newer, innovative solutions, such as debt-for-adaptation swaps, which allow developing countries to forgo debt repayment to international lenders and multilaterals in exchange for certified spending commitments on climate adaptation and resilience. Each of these tools, along with many others, will be needed to play a role in closing the climate-health finance gap.

Health Adaptation Finance Remains Underprioritized and Underfunded

Annual spending on climate adaptation more than doubled from 2018 to 2022—from USD 35 billion to USD 76 billion—about one-third of the level of anticipated need just to meet adaptation needs in emerging markets and developing economies. While some of this money is partially related to health system adaptation, it represents about 5 percent of all climate finance spending, and much of it is not directed toward health system adaptation.

Data source: Source: Climate Policy Initiative

Looking ahead

Successfully addressing policy and investment needs at the climate-health nexus will require calling upon a broad range of stakeholders across the public, private, and non-profit sectors, particularly in the health care and pharmaceutical industries, and encouraging frequent collaboration, ongoing research and development, and sharing of best practices. As governments seek to convert high-level plans into on-the-ground action, they must continue to meaningfully engage communities across all geographic and socio-economic divides to ensure that climate solutions are adaptive but also fit for purpose. Likewise, attention will need to be paid to short-term crises and needs alongside the long-term imperatives inherent to the climate struggle. To that end, key stakeholders need to consider the following priority actions:

- Equip health systems to prepare for climate change’s impacts on health. Aspects of health care including therapeutics, health infrastructure, and supply chains can be better prepared to face the climate-driven risks to health, from NCDs to extreme weather events, saving lives and making communities more resilient.

- Encourage and adopt technological innovation to address the climate-health nexus. Advancements in pharmaceuticals, digital health, surveillance and diagnostics, and even artificial intelligence can make it easier to expand and improve health care access while monitoring and counteracting climate-related health stressors.

- Build policy frameworks that enable international and domestic climate-health action. Health remains a secondary- or tertiary-level consideration in the climate change fight for most countries, but continued efforts to highlight the close connections between health and other aspects of climate change can help build political will and the resources needed to see plans through to fruition.

- Grow and sustain financial commitments to address health as part of climate action. Amid a major climate finance deficit, an expanded suite of adaptation finance tools can help close the gap. Likewise, well-targeted spending can deliver simultaneous progress across a host of policy goals, such as climate, health, nutrition, water security, economic development, and beyond.

Major international fora such as the World Health Assembly and COP30 present a powerful opportunity to energize and catalyze action in the climate-health nexus and bring together like-minded stakeholders with a common goal. The earlier such ambition turns into real-world policy, the greater the benefit for populations around the world.

By Phillip Meylan (Affiliate Researcher), Isabel Schmidt (Senior Policy Analyst and Research Manager), and Dr. Mayesha Alam (Senior Vice President of Research). Illustration by Harol Bustos.

This issue brief was produced by FP Analytics, the independent research division of The FP Group, with support from Viatris. FP Analytics retained control of the research direction and findings of this issue brief. Foreign Policy’s editorial team was not involved in the creation of this content..