Innovation and Investment to Transform Women’s Health Across Generations

Catalyzing economic growth, unlocking social gains, and strengthening resilience for societies around the world

SEPTEMBER 2025

This issue brief is part of a broader FP Analytics research project on women’s health with support from the Gates Foundation. See the full report here.

Investments in women’s health have generated transformative gains and already represent one of the highest-return opportunities for safeguarding lives and improving livelihoods. Yet, on average, women still spend 25 percent more of their life in poor health than men. Closing this health gap could save lives, improve quality of life, and add up to USD 1 trillion to the global economy annually by 2040. Moreover, the benefits of investing in women’s health unfold over years and ripple across generations and communities. The case for investment and action is both a moral and economic one.

Progress toward gender-equitable health care has been uneven, incomplete and, in a shifting funding environment, is now at risk. For example, access to voluntary family planning—a cornerstone of women’s health, agency, and autonomy—remains out of reach for more than 250 million women worldwide. Meanwhile, the global maternal mortality rate remains more than triple the target laid out in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These and broader gaps in women’s health are concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly least-developed countries (LDCs), but gender-, income-, and race-based inequities also persist in high-income settings.

Maternal Mortality Rates

Though maternal mortality rates are trending downwards, most regions have yet to reach the 2030 SDG target set in 2015.

Deaths per 100,000 live births

Neonatal Mortality Rates

Regions with large concentrations of least developed countries are far from achieving the 2030 SDG target set in 2015.

Deaths per 100,000 live births

Data Sources: UNICEF Maternal Mortality Dashboard (data from WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and UNDESA); UNICEF Neonatal Mortality Data

Additionally, policies and public investments related to women’s health continue to emphasize sexual and reproductive health and underprioritize sex-specific conditions like menopause and noncommunicable conditions like cardiovascular disease that impact women differently from men. This narrow focus neglects major drivers of health disparities and limits the full realization of comprehensive health care for women and its subsequent benefits for their children, families, and communities. Renewed and new investment addressing women’s health challenges across the life course are critical to sustain momentum and address persistent inequities.

This FP Analytics brief, produced with support from the Gates Foundation, analyzes opportunities and challenges across three key themes—investment and financing, innovation, and advancing equitable access to care—to understand how a renewed global commitment to women’s health can deliver transformative results.

Investment in women’s health pays health, economic, and social dividends for everyone

Well-placed investments in women’s health deliver multifaceted returns—from sharp reductions in preventable deaths in the short term to lasting gains in health, education, and economic well-being. Numerous existing strategies—including early cancer detection through regular screenings, expanded access to family planning, and periodic screenings for cardiovascular disease risk factors—have driven dramatic improvements in both health and economic output. For every U.S. dollar spent on women’s health, there is a three-dollar return in economic growth. Strides in women’s health also contribute to gains in children’s health, including the reduction of child mortality. Indeed, better health outcomes for women and children contribute directly and indirectly to better education, decent livelihoods, and longer, healthier lives for populations around the globe.

To illustrate, investing USD 1.15 per person per year in a bundle of interventions that include family planning services and emergency perinatal and newborn care can cut maternal deaths by 54 percent, neonatal deaths by 71 percent, and stillbirths by 33 percent. Better maternal health leads to improved child nutrition, cognitive development, and education, which are crucial to breaking the poverty cycle and unlocking economic gains for families, communities, and entire nations.

The case for family planning is equally strong. Meeting unmet contraceptive needs would save lives, reduce health care costs, and boost economic growth. Research shows that every U.S. dollar invested in family planning as the sole intervention delivers an average of USD 26.80 return on investment from health benefits, economic growth, and government savings. To unlock these potential gains and deliver results to women and their communities, targeted investments are needed.

Correlation between Cervical Cancer Screening and Mortality

Preventative screening for cervical cancer is highly impactful, but is far more common in high-income countries.

Data Sources: WHO Global Health Observatory, GCO Cancer Today

Current funding is inadequate to expand and build upon proven interventions

Increased and better-targeted investment is critical to sustain and accelerate progress in women’s health, but time-tested methods that save lives in high-income countries have not been sufficiently implemented in LMICs. For example, the United States has all but eliminated cervical cancer through early detection systems such as screenings and HPV vaccinations. Yet, while efforts to replicate that success globally are underway, cervical cancer remains the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide. In 2022, 94 percent of the 350,000 women killed by cervical cancer lived in LMICs.

Underinvestment in access to and innovation on women’s health care are distinct but related challenges. Women’s health reportedly receives only 2 percent of health care venture capital funding while research on women’s health also remains underfunded. In 2020, only 5 percent of global research and development (R&D) funds were dedicated to women’s health. These gaps in funding have persisted despite the strong potential for innovation and high returns on investment. For example, menopause affects 1 billion women globally but remains underfunded and underprioritized. Yet, 80 percent to 90 percent experience mild to severe symptoms as a result of hormone changes, many of which contribute to women leaving the workforce early and undermining economic growth. Policymakers, development institutions, industry leaders, and investors are overlooking a market that comprises half the world’s population, missing an opportunity for improved health and economic outcomes.

Some investors are catching on and seizing the opportunity that the sector presents. Investments in women’s health are increasing. In the past five years, 35 successful exits—four IPOs and 31 mergers or acquisitions—have underscored the sector’s strong potential for high returns. These and other investments hold enormous potential for the future.

Nevertheless, funding for women’s health has taken a serious hit from widespread cuts to foreign aid from high-income countries. Funding reductions and eliminations could shutter half of all women-led and women’s rights organizations in humanitarian settings over the remainder of 2025, with a direct impact on women’s health outcomes. The freeze on U.S. foreign aid alone will result in 34,000 additional pregnancy-related deaths in one year. Funding contractions are particularly alarming in fragile settings, where disruptions to services cause preventable deaths daily. Growing numbers of women and children now live in conflict-affected and climate-vulnerable areas, environments that carry their own implications for health: An estimated 64 percent of maternal deaths and 51 percent of stillbirths occur in countries facing humanitarian crises.

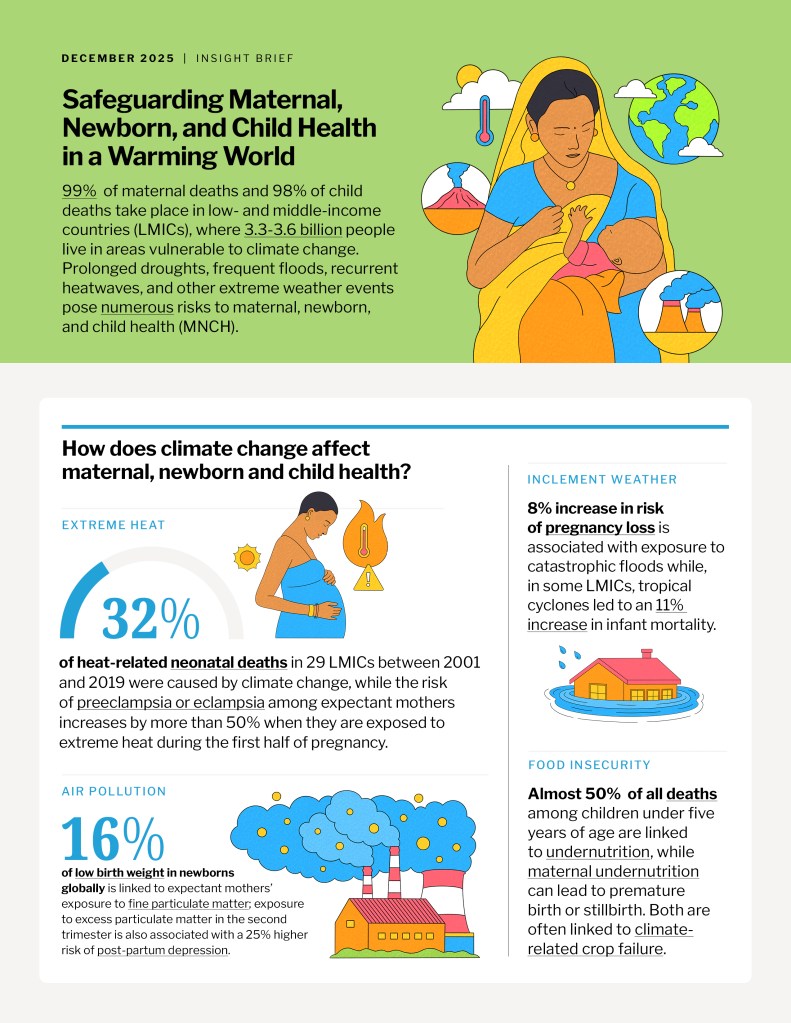

To read more on climate and women’s health, download the insight brief Safeguarding Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health in a Warming World.

With the retrenchment of foreign aid, creative models of financing are critical to enable innovation and partnership to close health care gaps. New public-private partnerships, blended finance, and catalytic capital can engender early-stage ventures and scale promising solutions to save lives and drive development. And these investments can be most impactful when targeted to proven interventions and novel ones supported by high-quality data and evidence.

Innovation is essential to pilot, scale, and expand new approaches to meeting women’s health needs

The state of women’s health globally calls for a surge in female-centered innovation that can meet and adapt to current and evolving health care needs, and address the full range of health concerns across a woman’s lifespan. Currently, the vast majority of the very limited R&D funding for women’s health focuses on cancer and fertility research. This focus is due in part to the historic exclusion of women from clinical medical trials: From 1977 to 1993, women of reproductive age were banned from clinical trials in the United States, and women are still largely underrepresented globally in trials. This exclusion and the narrow definition of women’s health have inhibited the understanding of sex-specific risks and gendered differences in conditions like cardiovascular disease, autoimmune disorders, and mental health, as well as the impacts of communicable diseases such as malaria and sexually transmitted infections both on women’s health and gender equity.

However, important and promising strides are being made. Digital tools and female technology (FemTech) are driving record investment in R&D for long-underfunded women’s health issues and broadening access to health services in LMICs while also promising major market potential. Self-injectable contraception, for example, has granted women more autonomy over their reproductive health and holds particular promise for women in crisis settings. FemTech could also help deliver lifesaving interventions to prevent noncommunicable diseases—responsible for the deaths of 19 million women globally each year—in resource-constrained settings. In South Africa’s Gauteng Province, for example, a pilot study tested whether combining clinical breast examinations with an artificial intelligence-enhanced diagnostic tool called Breast AI could improve screenings where mammography access is limited. Over six months in 2023, 1,617 women were screened. Breast AI identified four additional positive cases and reduced false negatives, compared with breast examinations alone, ensuring timely referrals and avoiding unnecessary surgeries.

A recent systematic review of 25 studies from Asia and Africa found that mobile health (mHealth) tools—such as mobile phone–based counseling, appointment reminders, and digital tracking—can improve maternal and neonatal health services in LMICs. Evidence points to gains in antenatal care attendance, skilled birth attendance, and postnatal follow-up, all of which safeguard the health, well-being, and lives of women and newborns. However, challenges remain, including disparities in phone ownership, technological misuse, and the need to ensure data privacy and security.

Critically, R&D for women’s and girls’ health needs to involve women and girls throughout the process—from ideation to trial to launch and scaling—to deliver better, tailored care. Achieving this means supporting female-led enterprises and female scientists. One example of this is Awaaz-e-Sehat, a voice-assisted mobile app developed by a female computer scientist in Pakistan. The app equips frontline health workers with a tool that detects early signs of high-risk pregnancy conditions through structured local-language prompts and real-time risk alerts. The app’s pilot phase shows immense promise; it has flagged symptoms of gestational diabetes and hypertension 40 percent of the time, compared with a detection rate of 7 percent among doctors in traditional settings. Pilots of this kind are crucial to bridging the R&D gap and innovating for women’s health.

Beyond technological innovation, it is also key to invest in R&D to treat underfunded and poorly understood conditions. Health conditions that predominantly impact women and girls—including endometriosis, anxiety disorders, and migraines—are disproportionately underfunded, compared to their estimated disease burden. Without the knowledge that comes from R&D, these conditions cannot be diagnosed, treated, and cured.

Scaling up R&D and innovations that serve women across their lifespans and address their full range of health needs will require catalytic capital from a range of stakeholders. Governments, philanthropies, and private-sector actors need to continue to safeguard progress on women’s health, address unmet needs, and ensure that women and girls across the globe can thrive. Public-private partnerships can help bring high-potential solutions to market by de-risking the R&D process and encouraging creativity and innovation within public and private research facilities.

Closing the knowledge and evidence gap is key to advancing equitable access to quality care

Within and across low-, middle-, and high-income countries, access to health care remains unequal, even when proven solutions to challenges exist. A child born in a high-income country has an average life expectancy at birth of 80, compared with 63 for a child born in a low-income country. In the United States, Black women are twice as likely to develop diabetes over the age of 55 and three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes, compared with white women. Women in all regions often face worse health outcomes than men. For example, studies conducted in the United States found that women are 66 percent more likely than men to be misdiagnosed and saw significantly longer delays between symptom onset and disease diagnosis than men across 112 acute and chronic diseases. These inequities are rooted in structural barriers such as gender bias in health care systems, a lack of access to health care facilities, prohibitive health care costs, harmful gender norms, and the insufficient presence of services.

Women’s health would benefit from more frequent, granular, and high-quality sex-disaggregated data on health. Progress is being made, but slowly. For example, the World Health Organization’s Global Health Statistics were not disaggregated by sex until 2019. Meanwhile, the available gender data needed to monitor the gender-specific dimensions of the SDGs grew from less than 25 percent in 2016 to 42 percent in 2022. Assuming a steady annual increase of 3 percentage points, it will take until 2041 to have complete data. Trends in scientific publishing are similarly positive but incremental. Over the past 10 years, the evidence on sex-related differences in health has multiplied, with publications on these differences doubling, but the gender health data gap persists, with ramifications for health outcomes targeted investments.

The shortfall of gender-specific health data transcends borders and socioeconomic lines but is most acute in LMICs. Developing an adequate bank of sex-disaggregated data will therefore require dedicated, coordinated efforts, both within and among countries. These efforts could entail nontraditional methods of data collection, including the use of citizen-generated data; providing capacity-building to governments to streamline gender-disaggregated data into national statistics; and partnering with community health workers (CHWs)—individuals who receive organized training to deliver frontline health services to their neighbors—to collect local, granular data on women’s health.

Improving access to care will require stronger primary health systems and sustained community engagement

Beyond closing the gender data gap, building more equitable health systems demands comprehensive approaches that address the systemic impediments to women’s health. The foundation for holistically addressing women’s health needs to be built on robust, integrated primary health care (PHC) systems. For example, in Senegal, strong national investments in child health—including a national immunization program delivered through PHC providers and CHWs—have reduced the mortality of children under age five by 70 percent and neonatal mortality by 41 percent since 2000. Without reliable PHC, targeted interventions will falter.

There are a range of demonstrated economic benefits as well. A recent study conducted in Kenya found that for every U.S. dollar spent on strengthening the country’s PHC system, USD 16 was saved, including costs associated with maternal morbidity. Strengthening PHC systems and increasing access to facility-based care can not only improve health outcomes but also increase enhance resilience to crises such as pandemics, climate-related disasters, and conflicts. Moreover, CHWs—alongside midwives—are a cornerstone of effective PHC, bridging gaps in access and delivering essential services in some of the world’s most underserved areas.

Returns on Investment for Key Women’s Health Interventions

Investing in women’s health delivers substantial economic benefits.

Data Sources: World Economic ForumMortality Data, Copenhagen Consensus, UNFPA, Rand

Ensuring that PHC systems deliver better outcomes for women requires reforming current practices and an expansion of proven interventions. Sufficiently resourced CHWs are one promising avenue for providing comprehensive women’s health care. CHWs—alongside midwives—are a cornerstone of effective PHC, bridging gaps in access and delivering essential services in some of the world’s most underserved areas. Evidence shows that CHWs improve maternal and child health, expand access to family planning, and provide critical prevention and care for noncommunicable diseases. They are equally vital in addressing infectious diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, managing up to half of the malaria burden in many countries.

Evidence shows that CHWs improve maternal and child health, expand access to family planning, and provide critical prevention and care for noncommunicable diseases. They are equally vital in addressing infectious diseases such as HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria, managing up to half of the malaria burden in many countries. Since CHWs are frequently women who provide home-based services, they can help reduce the stigma associated with seeking care and catalyze positive norm change. In Bangladesh, for example, research shows that female CHWs not only improved maternal and neonatal health outcomes, but their work also led women to exercise greater autonomy over family planning decisions and eased restrictive norms around women’s mobility and workforce participation. Allocating meaningful investment toward CHWs— including adequate salaries, training, and support—can improve women’s health, strengthen health systems, and create vocational opportunities for women.

Barriers to women’s health cannot be separated from other manifestations of gender inequality, nor can the inequalities in women’s access be separated from global, racial, and economic inequalities, which manifest in both low- and high-income settings. Ensuring that all women can access high-quality comprehensive care requires not only targeted interventions for women’s health but interventions that aim to improve women’s lives and reduce inequalities more broadly. Both types of interventions demand a cross-sector commitment.

Looking ahead: Securing long-term gains in women’s health care

A combination of targeted investment, innovation grounded in robust data, and efforts to expand equitable access to care has driven progress in women’s health. Together, these approaches have demonstrated the power of aligning financial resources, evidence-based solutions, and inclusive delivery systems to achieve lasting health and economic gains for individuals, communities, and countries. Maintaining and scaling this alignment will be critical to sustaining momentum, closing persistent gaps in both data and health outcomes, and realizing the broader development potential that improved health for women makes possible.

Investment in women’s health and the prioritization of women and children within broader health care policy and strategy are key to achieving not only health- and gender-related development goals but the entire SDG agenda. With five years until the 2030 SDG deadline, the time to act is now. Stakeholders can consider the following recommendations to advance equitable access to care, catalyze investments, and accelerate innovation:

Advancing equitable access to care

- Tackle structural inequalities that shape women’s health outcomes. Governments can integrate women’s health priorities into national gender equality, poverty reduction, and education policies, ensuring cross-sectoral coordination. Multilateral institutions can incentivize such integration by linking health financing to broader equity indicators. Civil society can help identify and address the intersection of health barriers with other forms of discrimination, ensuring the inclusion of marginalized women and girls.

- Invest in and scale proven solutions to women’s health challenges, including the use of primary health care (PHC) and community health workers (CHWs). Governments can formalize CHW roles within national health strategies, guaranteeing salaries, accreditation, and professional development. Multilateral organizations and donors can demonstrate the value of these interventions by collecting data, advocating, and funding pilot and expansion programs. Civil society and community-based organizations can strengthen CHWs’ links to local populations, building trust and increasing uptake of PHC services.

- Increase early detection and treatment in low-resource settings. Governments can incorporate noncommunicable disease screenings into maternal health, primary care, and CHW outreach, while investing in training and supply chains to ensure quality and continuity. The private sector can partner with governments to develop low-cost diagnostic tools, and donors can fund pilots that demonstrate effective integration in different health system contexts. The 2025 World Health Assembly Resolution on Strengthening Medical Imaging Capacity provides guidance on achieving this goal.

Catalyzing investment and finance

- Build strategic partnerships across stakeholders. Public-private partnerships can scale proven service delivery innovations such as telehealth-enabled prenatal care or CHW-led screenings for noncommunicable diseases. Governments can provide regulatory clarity and facilitate pooled procurement to reduce costs, while private companies can bring technical expertise and market reach. Non-governmental organizations and community leaders can help to ensure that solutions are culturally appropriate, accessible, and trusted.

- Mobilize catalytic capital to close the women’s health financing gap. Private-sector actors, multilateral institutions, governments, and donors can increase targeted funding for women’s health as both a health and economic priority, including through gender-responsive budgeting and financing. Philanthropic actors and development finance institutions can provide catalytic capital and help reduce investment risk in early-stage health innovations, especially those focused on underserved populations. Blended finance models and pooled funding mechanisms can help amplify private-sector investment, while dedicated women’s health investment platforms can direct resources to scalable, high-impact solutions.

Accelerating innovation and collaboration

- Promote equitable development of women’s health technologies. Policymakers, investors, and development finance institutions can direct capital toward early-stage and scalable FemTech solutions that center the contributions and experiences of diverse women to reduce bias and ensure contextual relevance for low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Technology developers can embed inclusive design practices, prioritize the collection of sex-disaggregated and intersectional health data, and incorporate bias-detection protocols into all AI-enabled tools. Governments and multilateral institutions can create enabling regulatory environments and procurement mechanisms that support equitable innovation. Private-sector actors can better ensure fair health outcomes by prioritizing the development of inclusive evidence-based solutions for under-resourced settings.

- Expand access to and harmonize the deployment of emerging health technologies to ensure affordability and equity. New technologies must be made affordable and accessible to all populations, particularly in low-resource environments. Developers can prioritize cost-effectiveness, offline functionality, low data requirements, and ease of use in settings with limited digital infrastructure. Donors and governments can expand access by funding the deployment and integration of technology into primary care, while ensuring that technologies are supported by sustainable financing models. Multilateral organizations can support broader adoption by helping countries harmonize regulatory frameworks and procurement processes, enabling the integration of proven tools into national health systems.

These recommendations outline a path toward closing persistent gaps in women’s health through coordinated, sustained action by governments, multilateral organizations, the private sector, and civil society. Achieving this vision will demand not just funding but also political will, technical expertise, and community engagement. Without a coordinated effort, the world risks entrenching existing inequities and missing the opportunity to harness women’s health as a driver of sustainable development. Targeted, gender-responsive investments can yield multigenerational gains—in health, education, economic growth, and resilience—benefiting not only women and children but societies and economies as a whole. With the deadline to meet the 2030 SDG targets imminent, stakeholders need to act decisively to scale proven solutions, integrate emerging innovations, and ensure that all women, everywhere, can access high-quality, comprehensive care throughout their lives.

By Dr. Emily Myers (Affiliate Researcher), Isabel Schmidt (Senior Policy Analyst and Research Manager), and Dr. Mayesha Alam (Senior Vice President of Research). Art direction and design by Sara Stewart. Illustration by Rosie Barker.

This issue brief from FP Analytics, the independent research division of The FP Group, was produced with support from The Gates Foundation. FP Analytics retained control of the research direction and findings of the issue brief. Foreign Policy’seditorial team was not involved in the creation of this content.